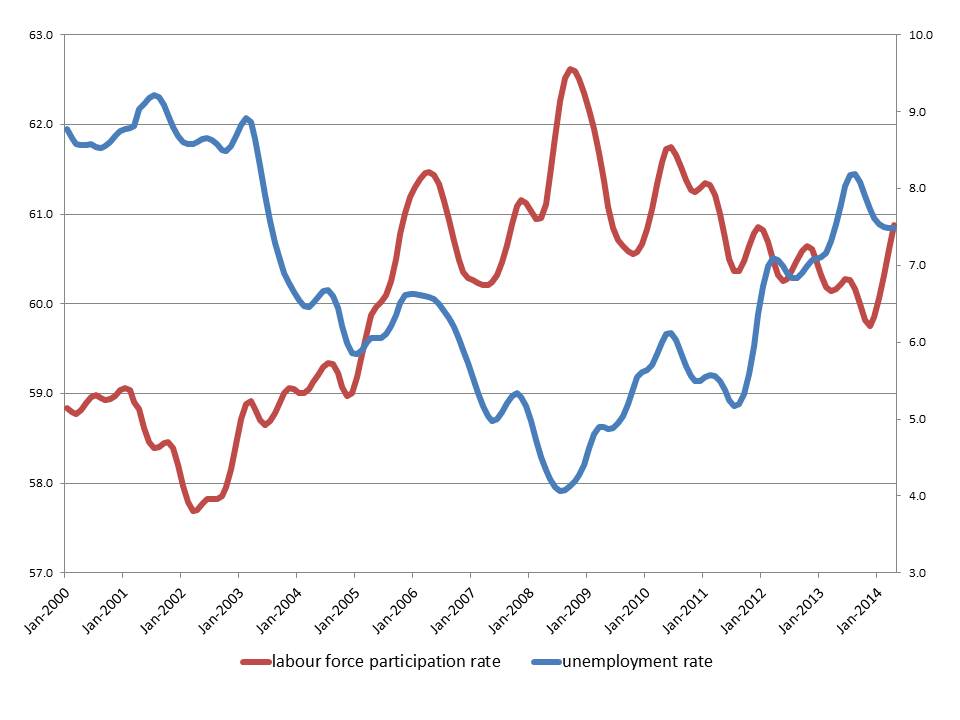

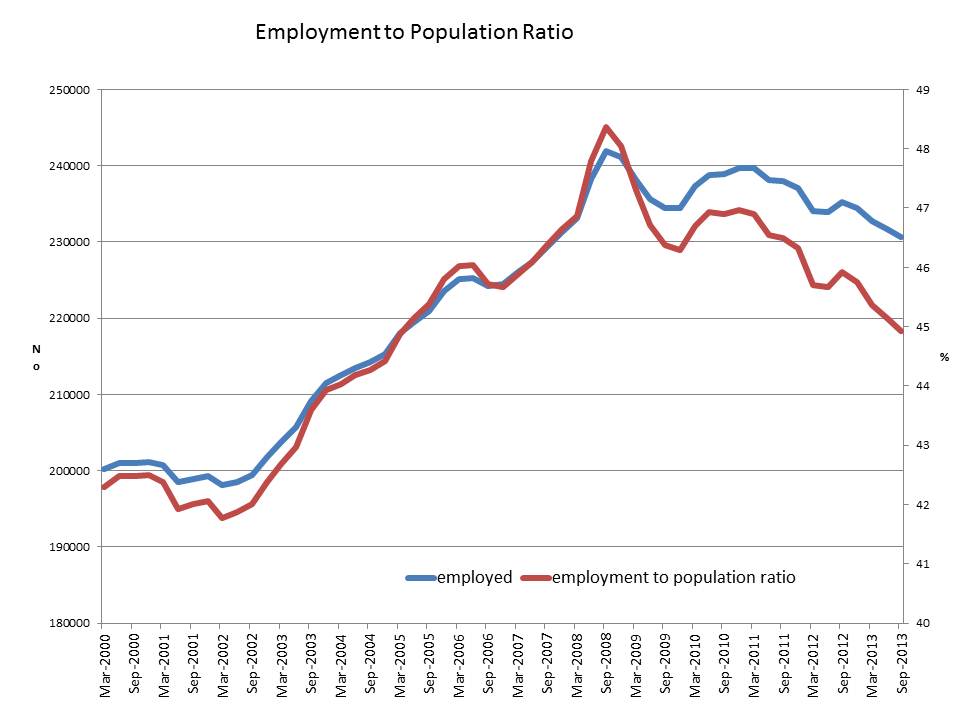

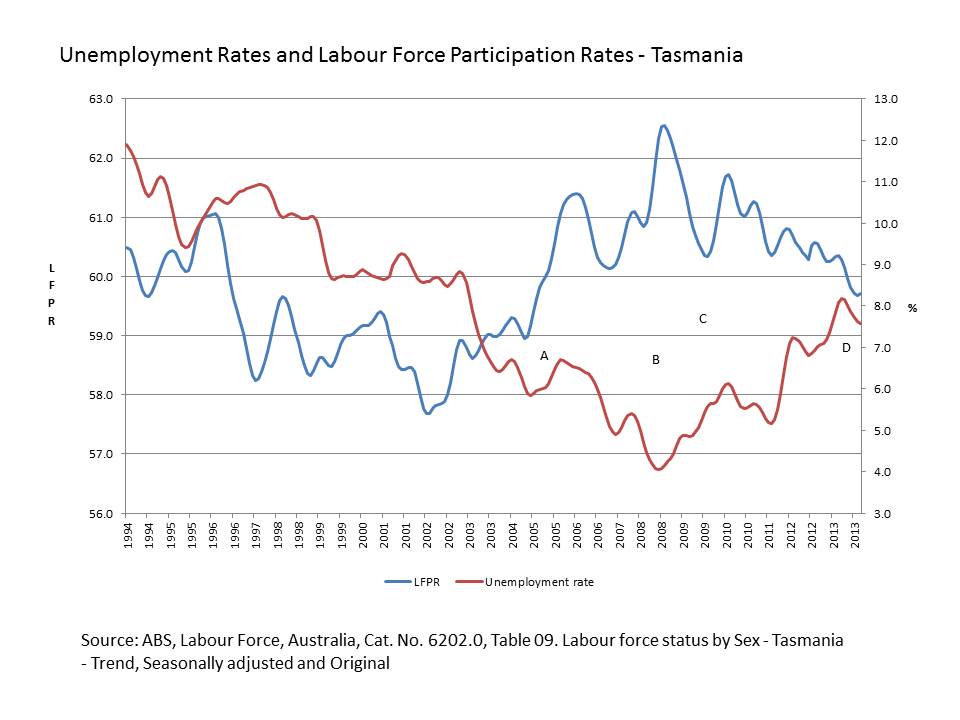

From June 2008 to September 2008, Tasmania's unemployment rate was 4.1 per cent and the labour force participation rate was above 62 percentage points for seven consecutive months. The total number of people employed peaked at 241,964 in October 2008 (its now 235,965).

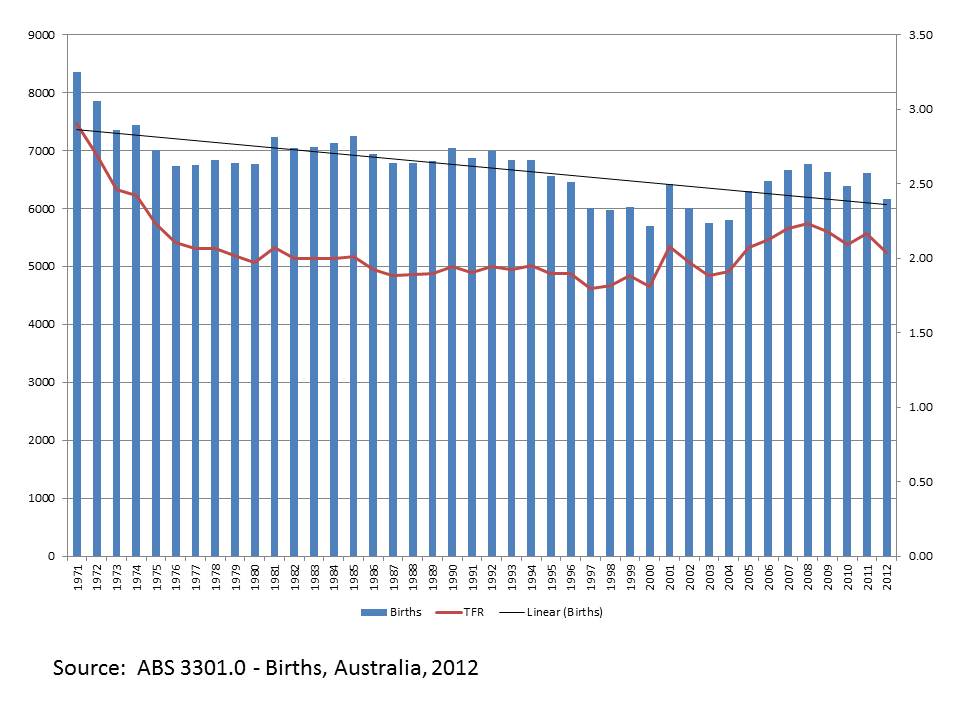

In the five year period to December 2008, employment grew by 29,672 people, or 14 per cent. During this same time, the population grew by 22,630 persons (natural increase 12,556, net overseas migration 7,105 and net interstate migration 2,969). Employment growing at a greater pace than population growth is an ideal situation for both the economy and society.

However, we know not long after that the GFC hit and the strength of the global economy deteriorated. Five years on, there are signs of potential recovery. The unemployment rate is now 7.5 per cent and participation is 60.9 percentage points. Employment is lower than its high in 2008 by 5,999 people yet at the same time, the population grew by over 12,000 people.

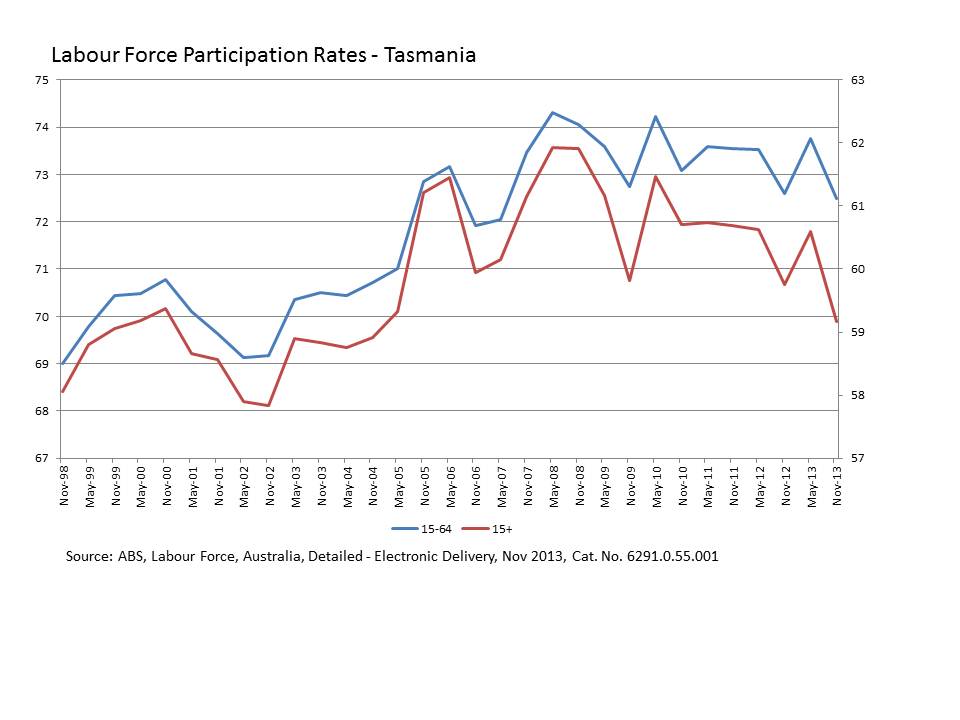

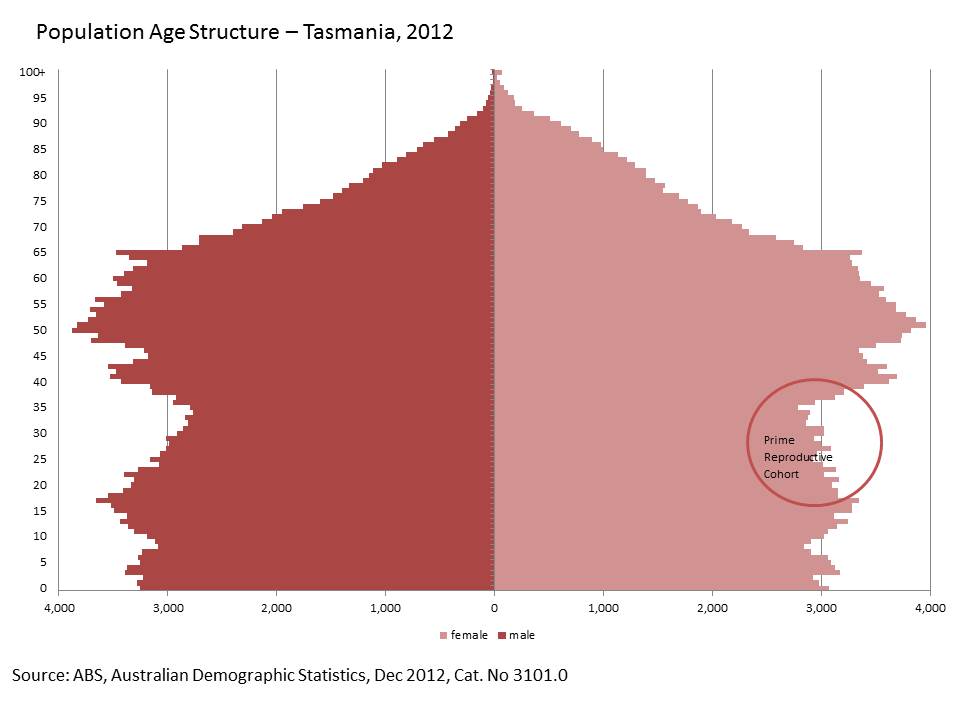

In terms of the states population, during the five year period 2003 to 2008 Tasmania experienced positive net interstate migration in three of those years. In the past 17 years, Tasmania has only experienced positive net interstate migration six times (the other three were in 2002, 2009 and 2010). Importantly, however, is that during these positive periods of net interstate migration, Tasmania experienced net interstate migration losses for the ages 15 to 29. So while Tasmania experienced population growth, this growth was contributing to the state ageing at a faster rate which will ultimately negatively impact on the state's employment to population ratio.

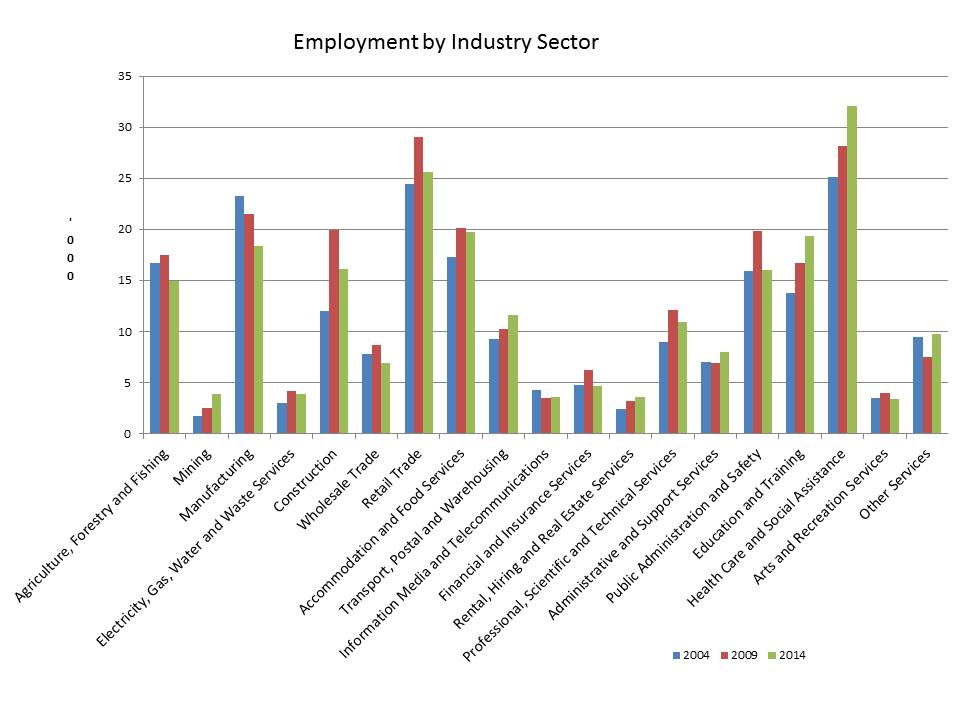

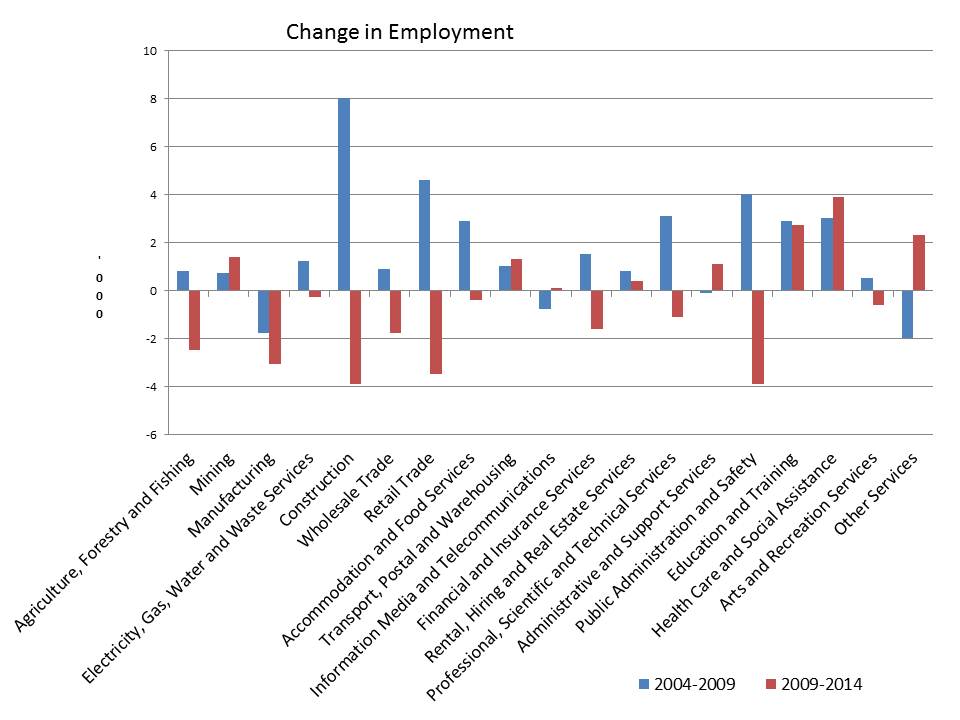

While Tasmania's largest employing sectors are health care and social assistance, retail trade and accommodation and food services, the greatest employment growth experienced in the five year period February 2004 to February 2009 was in the construction, retail and professional, scientific and technical services sectors. During this time, employment contracted in manufacturing, information media and telecommunications and other services.

Since the GFC, the greatest employment growth has occurred in health care and social services, education and training and other services (which returned to 2004 levels). The greatest contraction occurred in construction, administration and support services, retail and manufacturing.

Access to the island is likely to increase with an extension of the Hobart Airport runway and a re-prioritisation to passenger services by the TT-Line. The dropping of headworks charges, the introduction of a "Regulation Reduction Co-ordinator" and a renewed focus on streamlining the planning scheme/s will likely reinvigorate the construction industry. However, construction is a cyclical sector and will only create employment in the short term if not supported by efforts to achieve long term, sustained employment growth, through structural change and increased confidence in the private sector. The introduction of an Office of the Co-ordinator General to attract and facilitate investment in the state will assist this process, however its effectiveness will be dependent upon an appropriate budget allocation to proactively encourage investment in Tasmania. Also working in Tasmania's favour is an increasing global demand for agribusiness products and services, as recognised and supported by the current and previous Governments as a significant growth opportunity for the state.

Future employment growth will come from sectors experiencing organic growth (e.g. health, aged care, community care and child care largely resulting from an ageing population, the NDIS, and increasing participation in the labour market by mothers) and sectors receiving strategic support from the government (e.g. agribusiness). Increased demand for employment will also come from an increasing number of people retiring due to the ageing of the workforce. Some sectors and occupations are much older than others (e.g. health, education and farming). As the economy returns to sustained positive performance, employment growth will occur in consequential sectors (e.g. retail, hospitality, real estate and financial services).

Challenges for Tasmania's future economic prospects include fiscal constraints to proactively pursue investment opportunities, the perceived and actual risk of doing business in Tasmania, freight challenges and the potential acceleration of population ageing as a result of short term population growth (resulting in further deterioration of the employment to population ratio).

The ability of the government to provide for the Tasmanian population as it inevitably ages will be dependent on its ability to reverse the current downward trend in the employment to population ratio as well as maintain, or preferably increase, over the longer term.

Note: employment figures are total and are the sum of full and part time employment and in trend terms. Source ABS.