Tasmania's vital index (below chart) is a result of a number of factors: the total fertility rate (TFR) and its historic downward trend (and recent increase); the proportion of the population in the older ages; the number of young people who have moved into childbearing ages; and the effect of immigration, which normally consists of workers and their families who are themselves in the childbearing ages. In Tasmania's case net interstate migration in the childbearing ages has historically been negative, while net international migration in the childbearing ages has been positive. However, interstate and international migrants have differing fertility patterns.

|

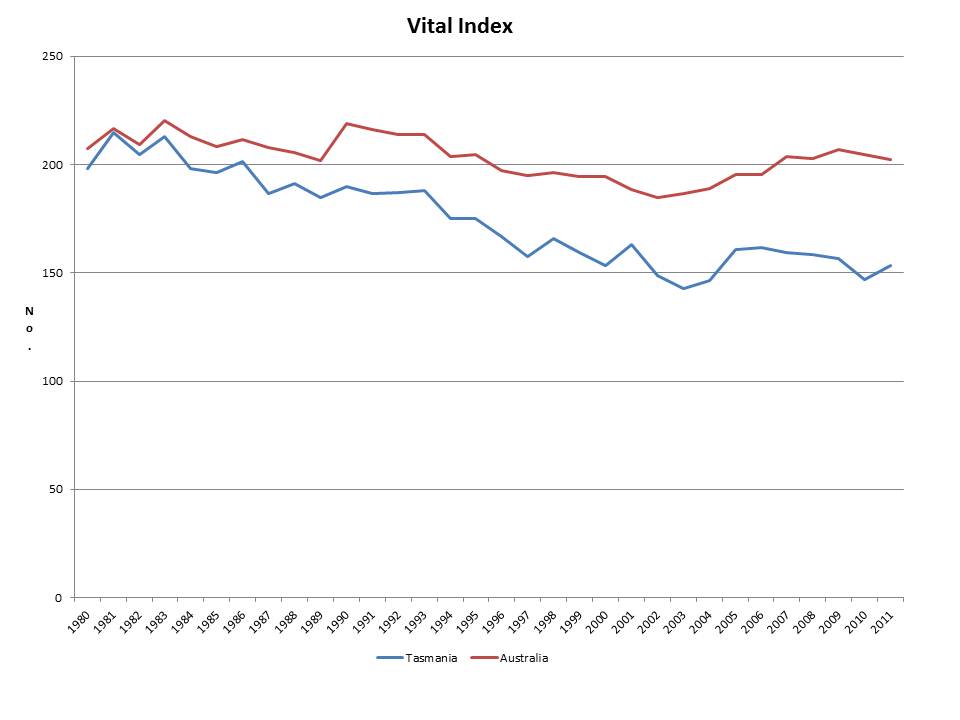

The vital index, the annual number of births per 100 deaths, is a simple measure but can often be eye-opening. In fact, the measure provides a valuable insight into population dynamics. A population's composition and size (and growth rate) is influenced by the number of births and deaths (the difference being 'natural increase' (or decline)) and migration. In Tasmania's case, migration includes both international migration and interstate migration. Tasmania's vital index (below chart) is a result of a number of factors: the total fertility rate (TFR) and its historic downward trend (and recent increase); the proportion of the population in the older ages; the number of young people who have moved into childbearing ages; and the effect of immigration, which normally consists of workers and their families who are themselves in the childbearing ages. In Tasmania's case net interstate migration in the childbearing ages has historically been negative, while net international migration in the childbearing ages has been positive. However, interstate and international migrants have differing fertility patterns. As the Tasmanian population continues to age at a faster rate than the rest of Australia (as a result of interstate migration patterns), it is likely that the state's vital index will continue it's (historic) downward trajectory. In the event that Tasmania's 'natural increase' becomes 'natural decline', any growth in the size of the population will be dependent on net increases in migration, which also has the potential to reverse the natural decline - subject to the age profile of the migrants.

0 Comments

The human element of age discrimination, immigration and over qualification in the labour market5/7/2013 Last week I attended the cepar International Conference on Population Ageing and following a long day of presentations and networking a group of us decided upon an impromptu dinner out nearby. Hailing a cab as you do, I jumped in the front seat as I find people interesting and enjoy speaking with taxi drivers. I didn't need to initiate conversation as the driver asked me what had brought me to be at the Uniiversity of NSW. Explaining I was attending a conference he asked me what I do. Keeping it simple I replied that I am a researcher in population ageing. He then asked if I was doing a PhD. Mildly taken aback I said yes, that I am, and I am researching the utilisation of skills in the labour market in response to the challenges of population ageing and the proposed 3Ps solution. He then asked if I asked people why they wanted to work. I advised him that I am a quantitative researcher and so do not interview people. He told me that was my mistake and proceeded to tell me his story. An Eastern European immigrant in his sixties with three degrees, one of which in engineering, from the very university at which I was attending the conference. He has never been able to get a job in Australia to match one of his qualifications and so has to drive taxis to make a living. By this time we had arrived at the restaurant we had booked, and all I could do was apologise to this highly articulate, obviously educated man, and wish him all the best. I wish I had been able to ask him more (qualitative) questions about why he wanted to work and also why he thought he couldn't get work in Australia, but instead I headed off for a night of networking with other population ageing researchers. Often we get wound up in the technicalities and policies surrounding population ageing and completely fail to consider the human element. A lesson to be learned. Government and business believe that a solution to population ageing, stagnating economic growth and skill shortages is increasing immigration. In fact, 80 per cent of the population growth projected in the 2010 Intergenerational Report will come from immigration and their yet to be born, highlighting the reliance of government on population growth to stimulate demand. Opponents to population growth raise concerns to the carrying capacity of the nation which extend to environmental and social consequences. However, there is another concern, that is, the economic opportunity cost of the current, and projected, high levels of immigration redirecting public monies to city-building infrastructure rather than productivity-enhancing initiatives.

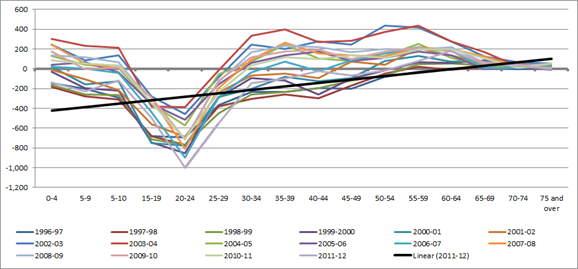

While immigrants on employment visas (as opposed to humanitarian and family visas) tend to be younger and more educated that the domestic population, there is little evidence that they are meeting the needs of employers in terms of skill shortages in regional and resource boom areas. Most migrants flock to the metropolitan areas of Sydney and Melbourne, and given the conditions of the visa preventing access to welfare benefits in the first two years of arrival, migrants need to accept any employment offer, often crowding out domestic workers which at times also results in a dampening effect on wages, particularly in a competitive employment market as we are now experiencing. It is estimated that migration contributes around 100,000 migrants to the workforce every year; however in 2012 only 115,000 jobs were created in Australia. Not only are migrants not meeting skills shortage requirements, but their mass contribution to population growth not only puts pressure on existing infrastructure and pushes up costs, it creates further skill shortages in non-critical jobs to meet the demands of an increasing population, ‘justifying’ further high levels of immigration. There is also evidence that the current high immigration and settlement in metropolitan areas is influencing domestic migration and the sea and tree change phenomena, creating similar infrastructure bottlenecks in regional and rural areas as being experienced in cities. To cater for this increasing demand, governments (federal, state and local) are required to provide the necessary infrastructure and services to support the population (as expected from a first world country). Given there is not a bottomless bucket of public money to spend, governments must decide how best to direct their revenue to support its population. For a nation projected to grow from a population of 23 million in 2013 to 36 million in 2050, this spend is currently committed to city-building infrastructure. This is despite the fact that the Commonwealth Government identifies in the 2010 Intergenerational Report that higher productivity is the key to balancing the needs of a changing demographic. Until the government determines the appropriate level of immigration to meet the needs of the current population, public money will be directed to supporting population growth as a result of immigration rather than to productivity-enhancing initiatives, such as information telecommunications, education and training, innovation support, research and development and regulatory reform. As a consequence, it is likely that Australia will continue to report woeful productivity performance. Tasmania recorded its worst net interstate migration loss in 12 years for the financial year 2011/12, losing 2,552 persons over the 12 month period, compared with 47 the year before and gaining 322 the year before that (2009/10). From a net migration perspective, Tasmania has historically always experienced a net loss in the younger ages of 15 to 29, seeking education, employment or life experience opportunities. Historically, the state has always experienced a net gain in the older ages of 45 to 75 and over, contributing to the rate of ageing. However, for the year 2011/12 the state experienced losses in all age groups from 0 to 54 and also, for the third time, a loss in the 75 years and over age group. This is evident in the below diagram illustrating Net Interstate Migration for Tasmania by age group from 1996/97 until 2011/12. It is easy to assume that this significant loss is the result of high levels of Tasmanians leaving the state in search of opportunities elsewhere. However, this is not the case. Net migration movements are the difference between arrivals to the state and departures from the state. The cause of the recent net migration loss is actually a greater decline in the number of arrivals to the state, rather than a significant increase in numbers leaving the state. Furthermore, while there has been slight increases in the numbers departing for each age group for the past three years, since data collection began in 1996/97 the numbers have been trending downwards for all age groups apart from those 55 to 75 and over (which are comparatively small in number). However, arrivals to the state have also been trending downwards over this time, again apart from those 55 to 75 and over (which are also comparatively small in number). This means that there have not been enough arrivals to the state to replace the ones who are leaving. Interestingly, but not surprisingly, Tasmania experienced its greatest net migration gains from 2002/03 to 2005/06 when arrivals peaked for all age groups and departures were at their lowest, coinciding with the relative economic prosperity the state and nation were experiencing.

Importantly however, 10,182 people arrived in Tasmania during 2011/12 (compared with a departures of 12,738). Of these arrivals, the largest group was those aged 25 to 29 (1,156 people or over 10 per cent of the total arrivals), closely followed by those aged 30 to 34 (938 people). While more people did leave the state in these age group than arrive, it is indicative that young, prime working age people still move to Tasmania, and more do so than in any other age group. The challenge for Tasmania is to reverse the recent slight increase in the numbers departing the state and maintain arrivals in order to return the state to positive interstate migration movements. |

Archives

April 2023

Categories

All

|