Population ageing is more often than not viewed negatively. This is an over-reaction. Population ageing presents challenges resulting from change. Just like any change, government and society need to adapt and innovate to capture the opportunities attached to that change.

The problem with population ageing is not that there are too many older people but that there are not enough young people to 1) provide the products and services required by a changing demographic and 2) pay tax to fund the increasing demand for publicly funded services (e.g. health and aged care and pension entitlements).

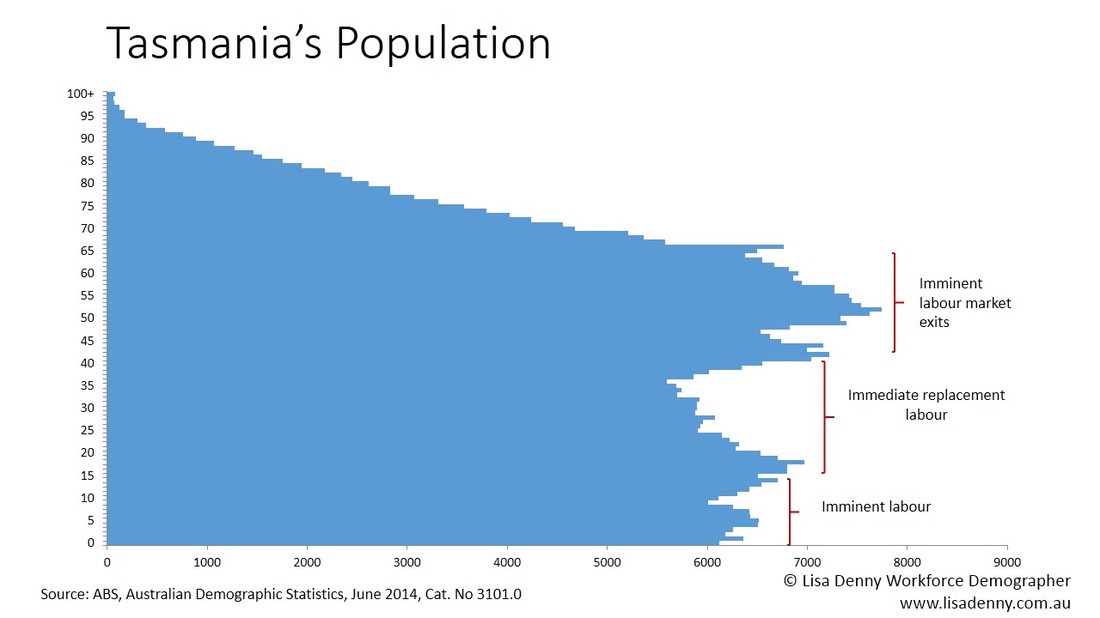

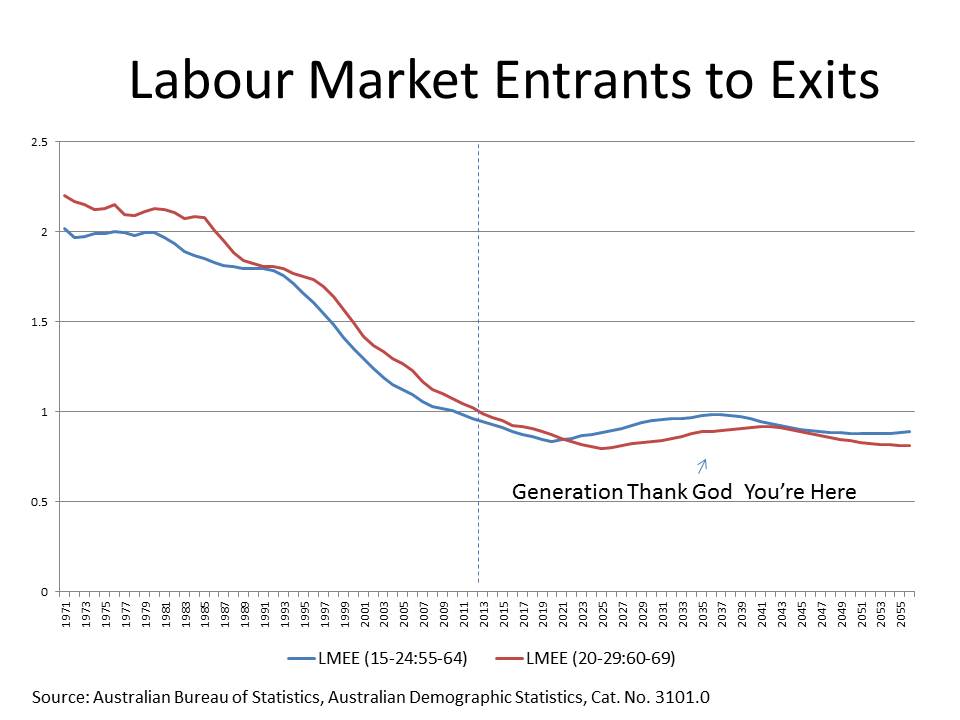

The below figure illustrates the imminent loss of workers from the Tasmanian labour force due to retirement (or exit from the workforce), the immediate replacement labour (those aged say 25 to 45) and the imminent labour market entrants - our youth. Each of these cohorts are significantly smaller in size than the cohort exiting the workforce.

Over the next 15 years in Tasmania over 100,000 workers will exit the workforce (based on the average age of retirement over the past five years - 61.5 years - as identified by the ABS in their Retirement and Retirement Intentions Survey). This exodus creates employment opportunities for our youth.

Some of the jobs of these older workers may need to be replaced, some may not, but an older population will also transform the consumer market and require new jobs to be created.

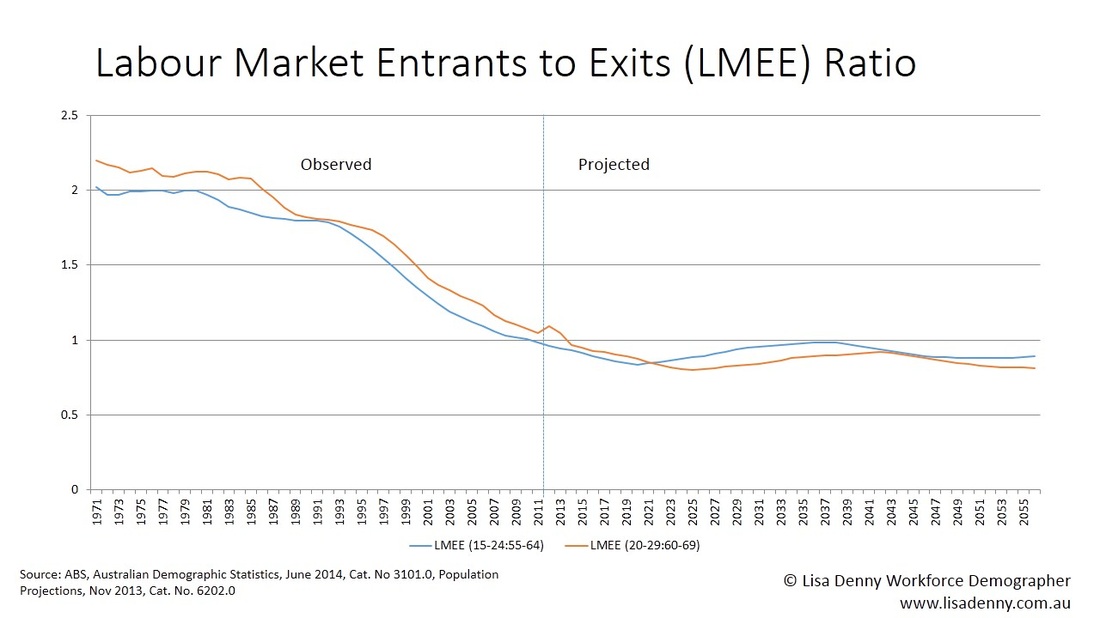

In Tasmania, we do not have enough people in the younger population (aged under 45) to replace these older workers, highlighting the critical importance of ensuring we shape and nurture our youth to take advantage of these opportunities. The ratio of labour market entrants to labour market exits in Tasmania is less than one, and has been since 2011. This means that for every person aged between 55 and 64 (assumed labour market exit age) there is less than one person aged 15 to 24 (assumed labour market entry age). This ratio is projected to continue. In addition, this measure of future labour supply does not consider the complement of education, training, skills and experience which will be essential from a potential working population.

This is where smart, timely and informed investment in education, training and skill development is required. As a State, we have a window of opportunity to to get it right.

1) Recognise that ageing workforces will result in a transformation of the workforce from one which is older with lower levels of educational attainment but life long experience to a younger workforce with high(er) levels of educational attainment but lower levels of applied work experience.

2) Industry, regions and organisations need to undertake extensive workforce planning to identify future demand, profile their workforce (by age, occupation and exit intentions) and identify critical job roles which have the potential to impact on growth and training capacity and then invest accordingly.

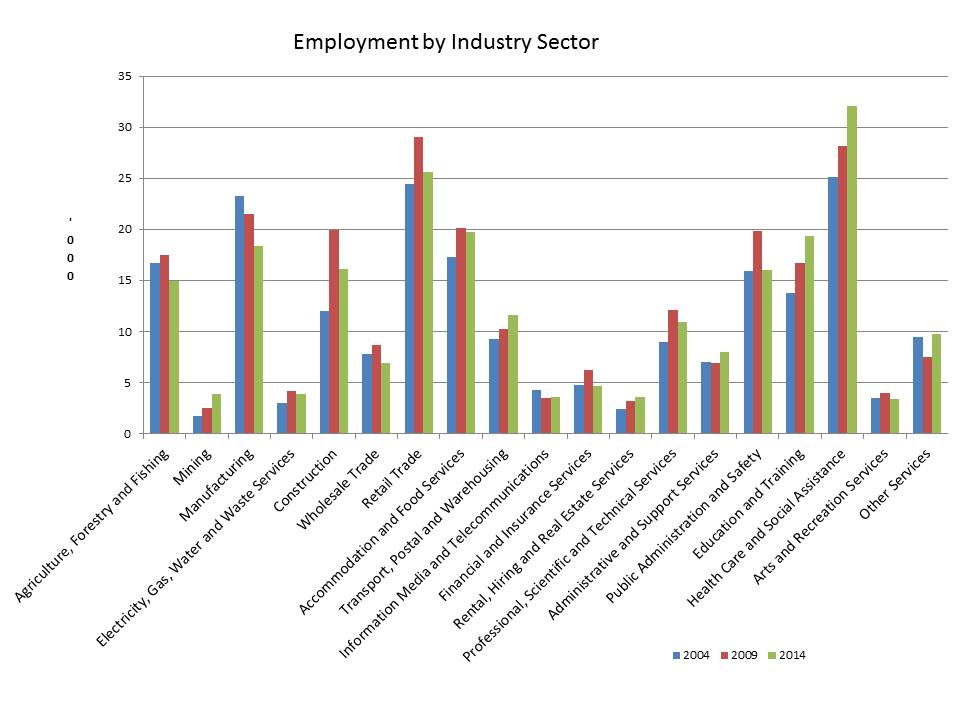

3) Acknowledge that wealth creating industries may not necessarily be job creating industries. As such it is important not to ignore the domestic economy and the demand within the population. There is already a deficit in the provision of care with an ageing population and the roll out of the NDIS will extend this deficit. Care related jobs are real jobs, with real skills and real wages.

4) Ensure investment in education and training is informed by demand - i.e. industry led with an employment outcome. This will increase efficiency in education and training investment and reduce the mismatch between educational attainment and job creation.

5) Recognise that social services, equity policy and 'second chance learners' also deserve an employment outcome opportunity.

Tasmania's ageing population is creating employment opportunities - both in replacement labour for ageing workforces and changing demographic demand - but the ability to capture this opportunity is dependent upon ensuring that investment in education and training matches changing employment demand. Our youth are not round pegs who will fit into round holes - they need to be appropriately shaped.