In the lead up to the event Salt stated in an Opinion Piece that

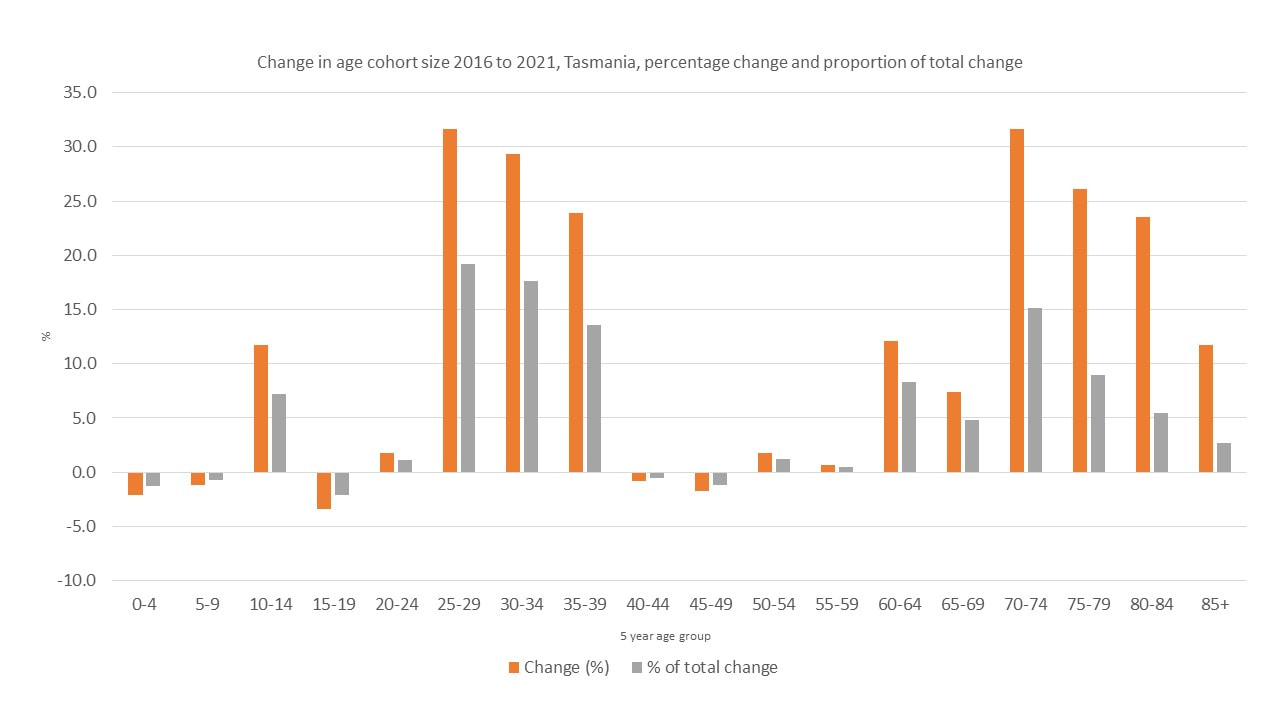

- The pandemic triggered the homecoming of 27,000 expat Tasmanians, lifting the state’s population by 5 per cent in one fell swoop.

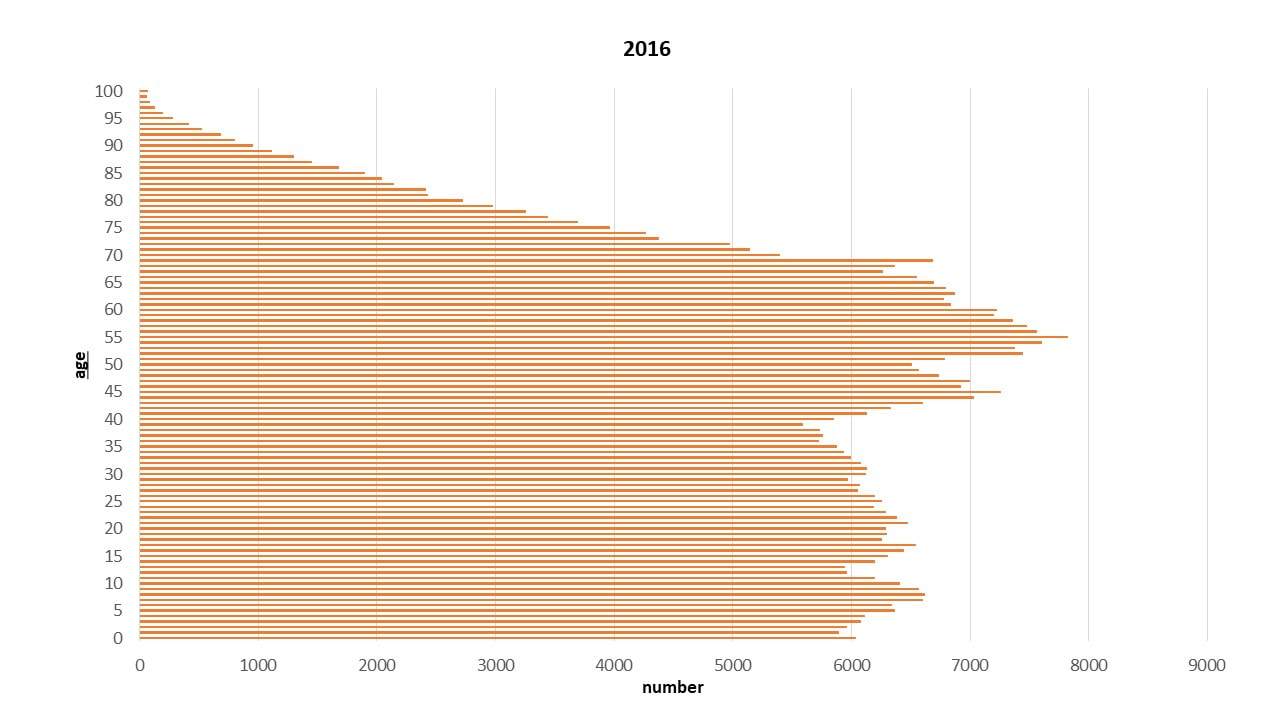

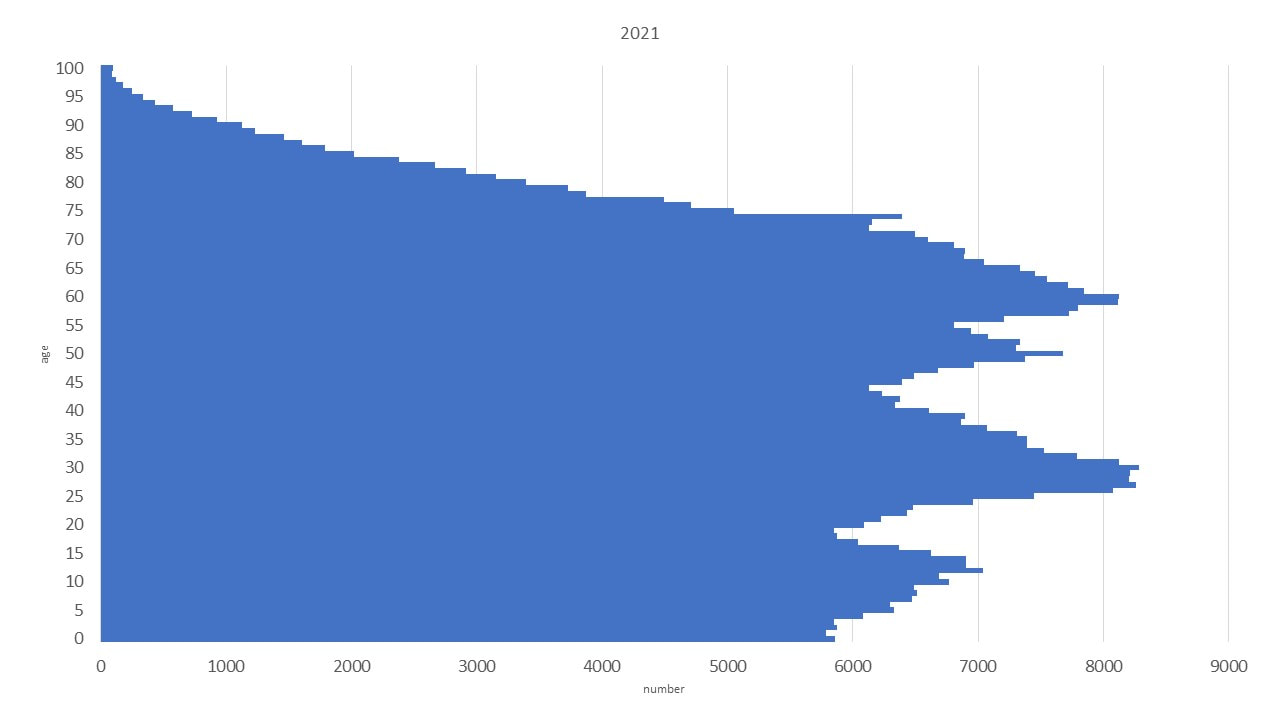

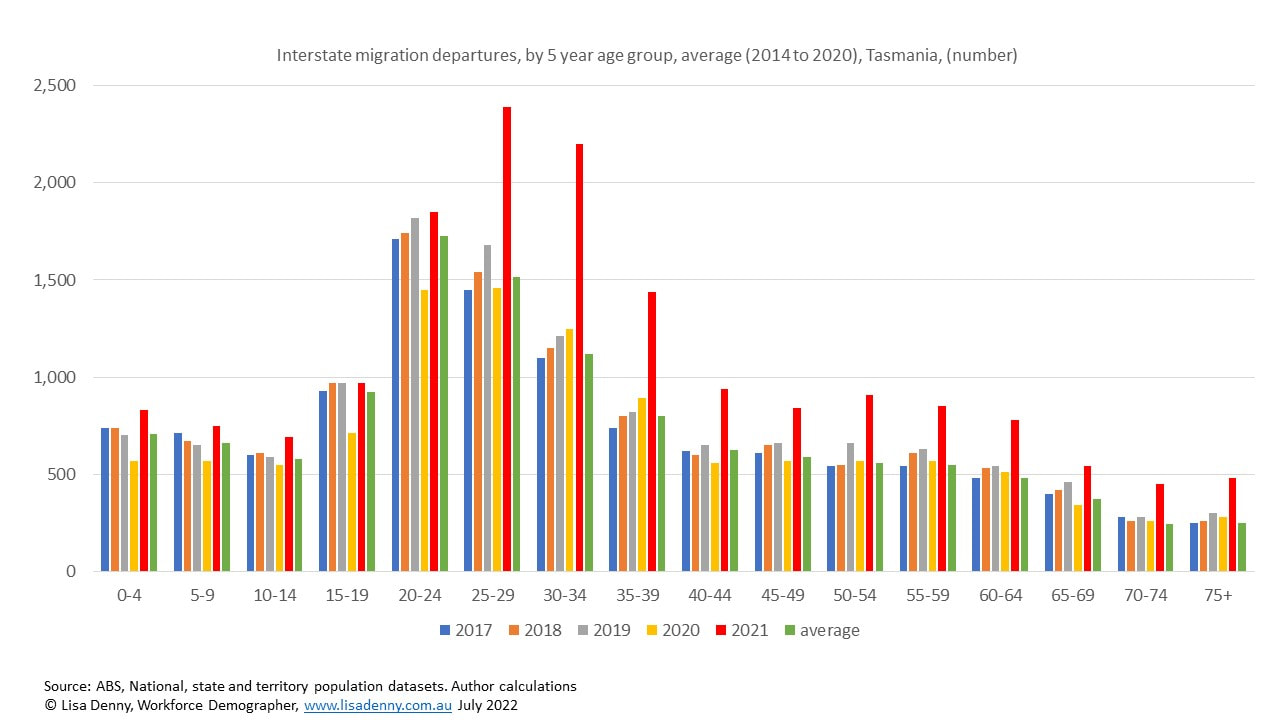

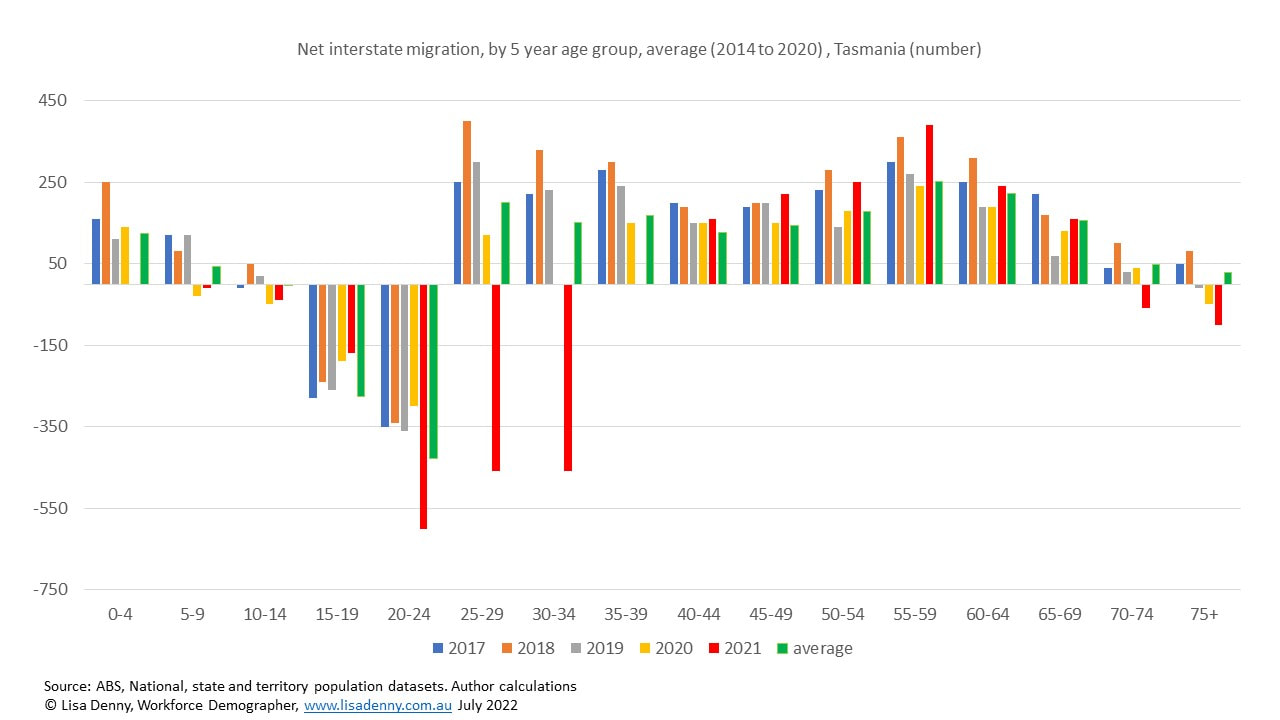

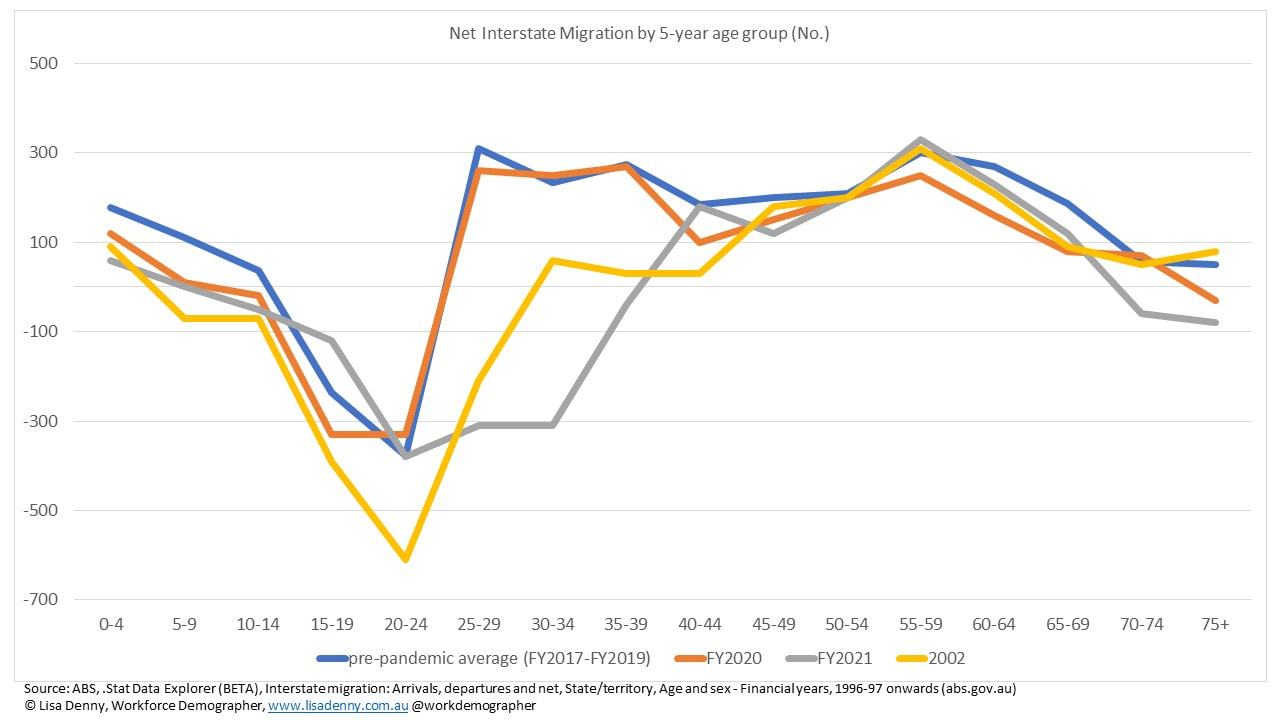

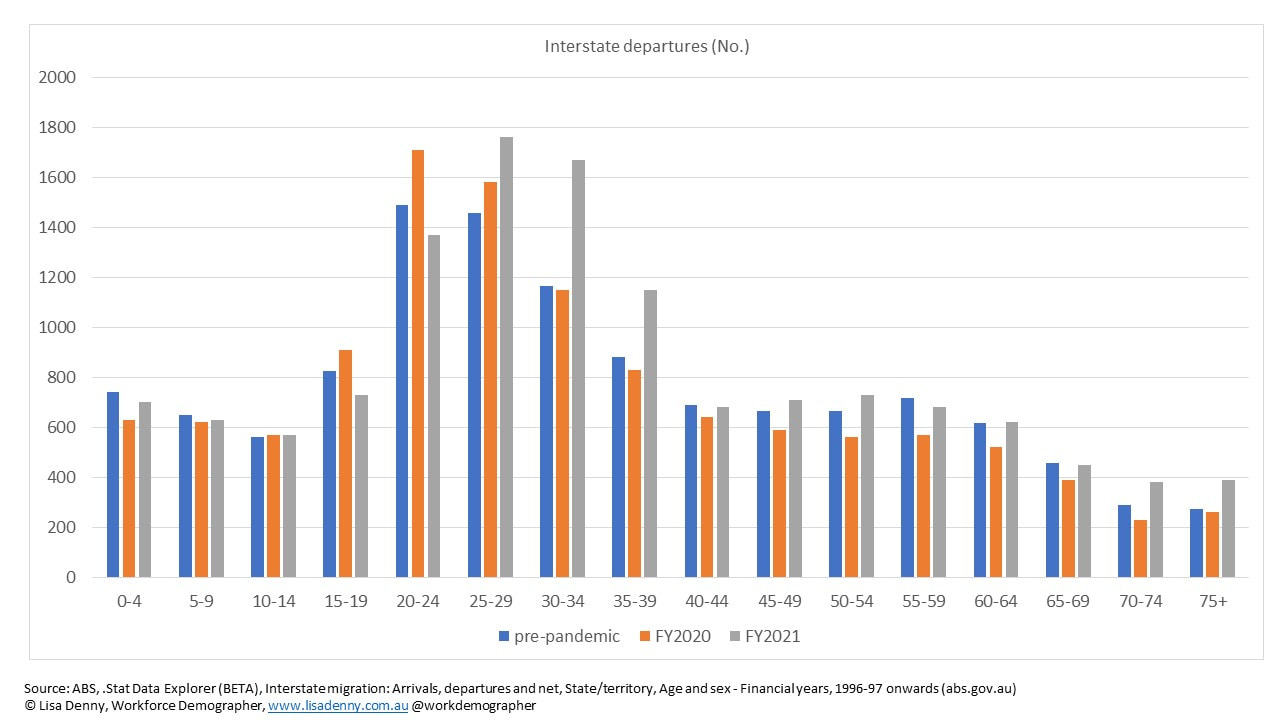

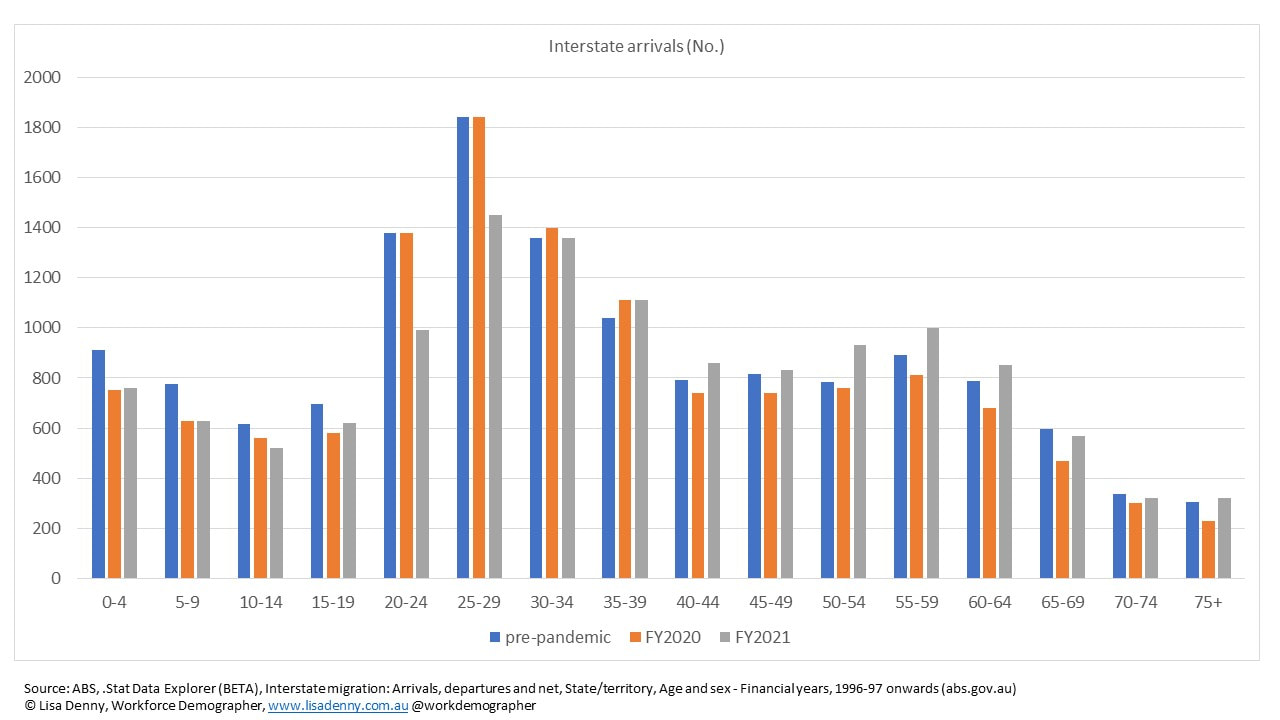

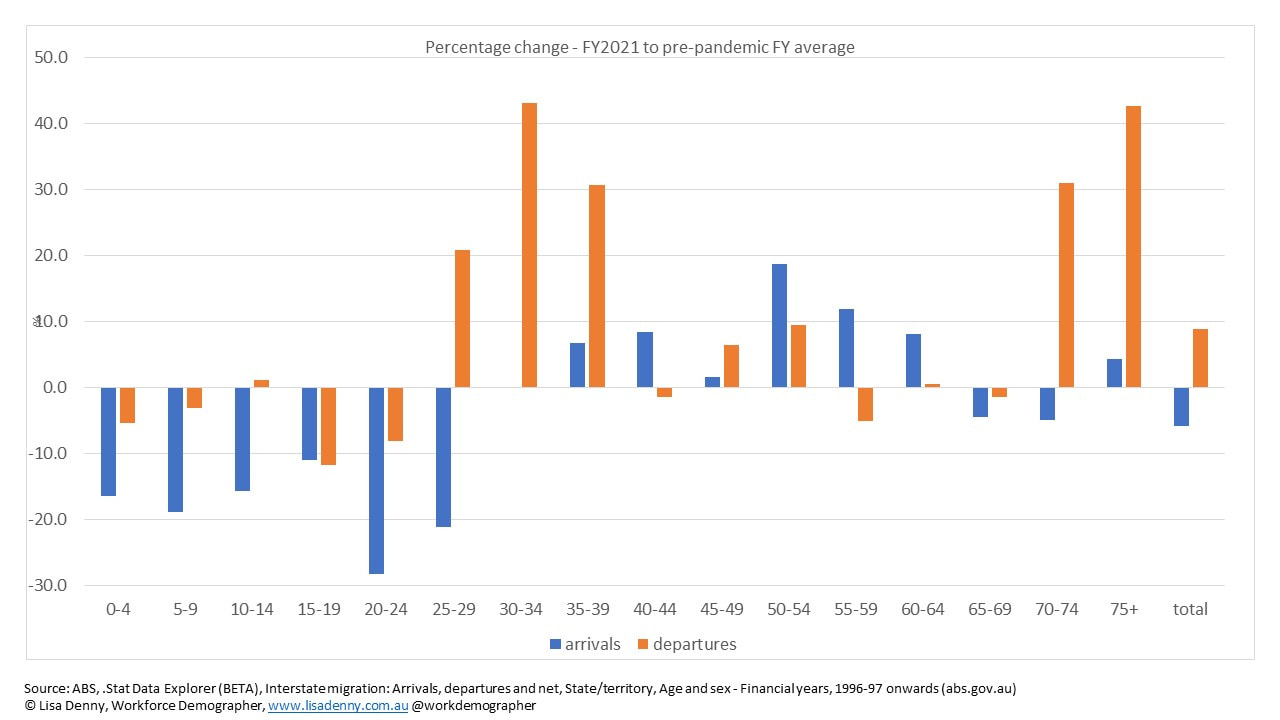

- These home-comers aren’t 20-something backpackers cutting short a grand tour of Europe; they’re 30-something and 40-something skilled workers with work history, contacts and, presumably, some level of capital.

- My argument is that Tasmania’s demographic turnaround, [is a] pandemic injection of skills, youth and energy.

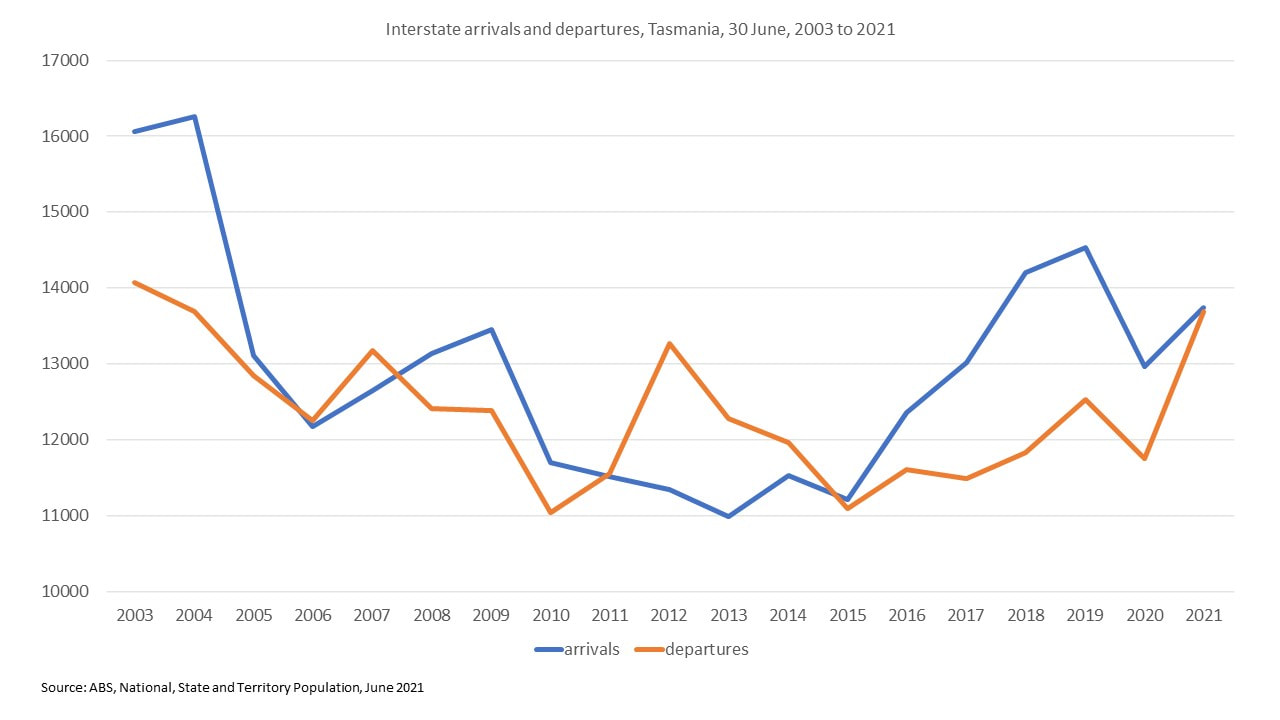

- Tasmania’s demographic outflow has flipped and is now heading straight for us in the form of an inflow.

Here’s the reality check.

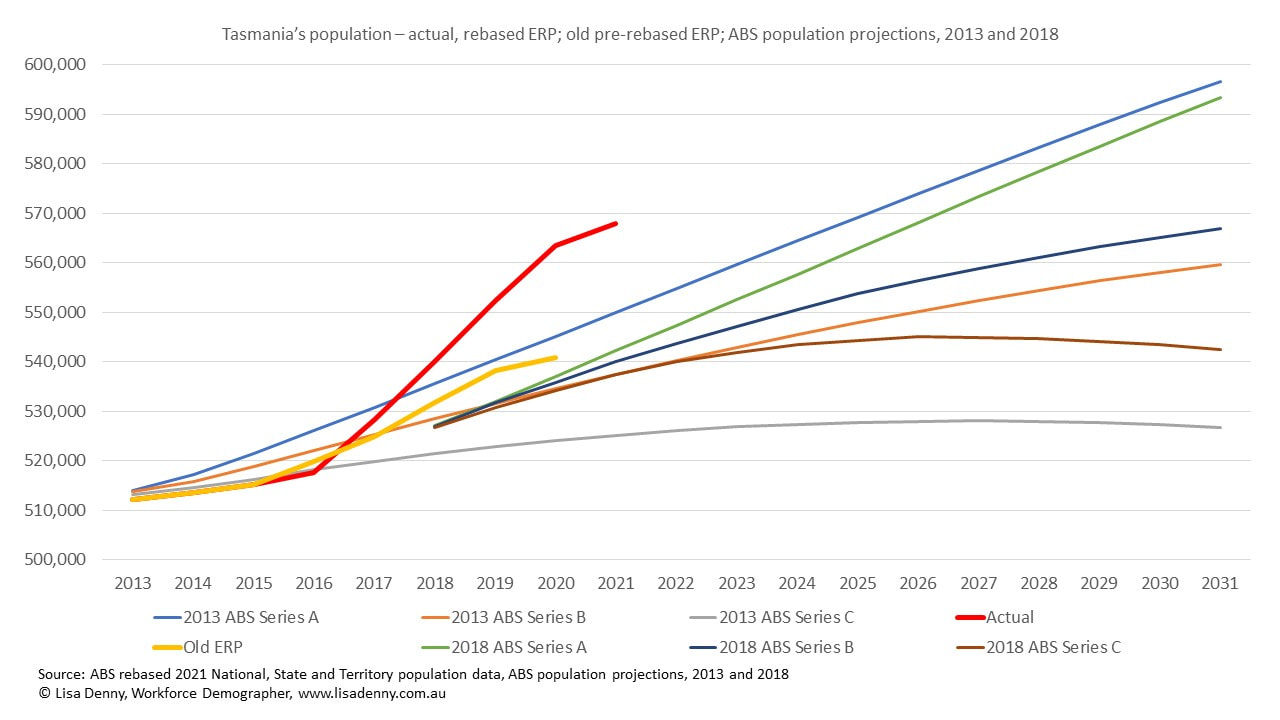

After every Census of Population and Housing, the ABS ‘rebases’ the population. Rebasing is the process of updating population estimates for the five years between Censuses, to incorporate information from the most recent Census. This is because the Census provides an actual count of Australia’s population whereas the ERP between Censuses is estimated based on administrative data – birth registration, death certificates, change of address data with Medicare and overseas arrivals and departures. Following each Census, revisions are made to the estimates for each quarterly and annual period in the previous intercensal period, this is referred to as ‘rebasing’.

The ERP includes all people who usually live in Australia (regardless of nationality, citizenship or visa status).

During this rebasing process for Tasmania the ABS discovered an undercount; Tasmania’s ERP was around 26,500 larger in size than had been estimated since the 2016 Census – equivalent to 4.9% larger. Tasmania’s population actually grew by around 9.7% rather than the 4.3% the pre-rebased ERP suggested.

Most of this undercount are not expats nor home-comers returning to Tasmania during the pandemic, but explained by overseas-born, young working age people who are likely to be on temporary visas and therefore not captured in internal migration movements. This is because they do not have access to Medicare – the primary data source for internal migration movements.

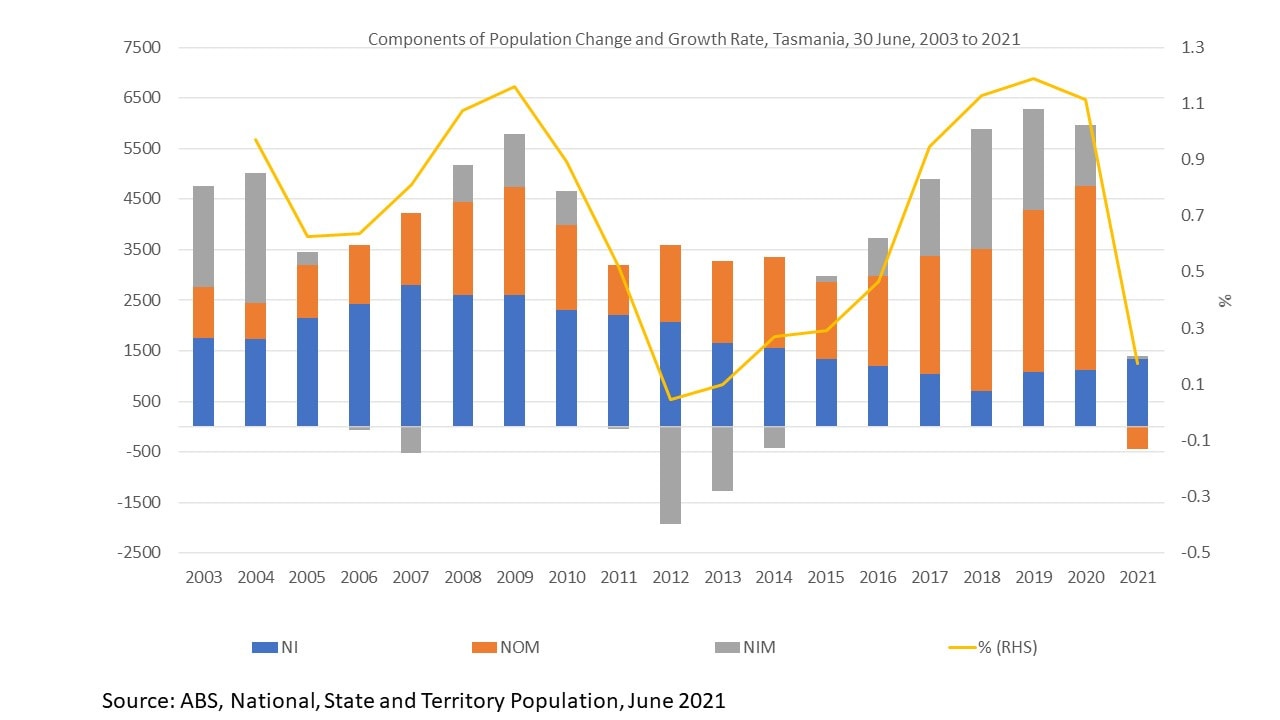

Also, most of Tasmania’s population growth since 2016 occurred prior to the pandemic. Overall, it grew by around 47,000 people - the sum of births, less deaths, plus interstate arrivals, less interstate departures, plus overseas arrivals, less overseas departures.

Of Tasmania’s total population growth since 2016, 89% of it occurred prior to March 2020. Since the onset of the pandemic, population growth has been 10,044 in total, averaging an annual rate of 1.0% ranging from 2.03% in June 2020 to 0.58% in September 2021.

Of those residing in Tasmania at the time of the 2021 Census and who lived overseas five years prior (approx. 19,300 people), 82% were not Australian citizens, and of those 77% were aged between 20 and 39 years). Additionally, approximately 33,300 Australians and 11,000 non-citizens moved to Tasmania from interstate during the same period. Around 29,000 people lived in Tasmania five years prior to the 2021 Census and now live interstate. Of these, 90% are Australian citizens, and 10% are non-citizens, the majority in the younger, working age groups. The Census does not capture those people who used to live in Tasmania and now live overseas.

During the onset of the pandemic there was an initial increase of Tasmanians returning from overseas, to provide a net gain of 710 people in 2019/20, this reduced to a net gain of 70 in 2020/21 and a net loss of 70 in 2021/22.

Most of the overseas migration gain since March 2020 has been from seasonal workers from the pacific islands who were unable to return home during the pandemic. However, international students on temporary visas are now increasing again.

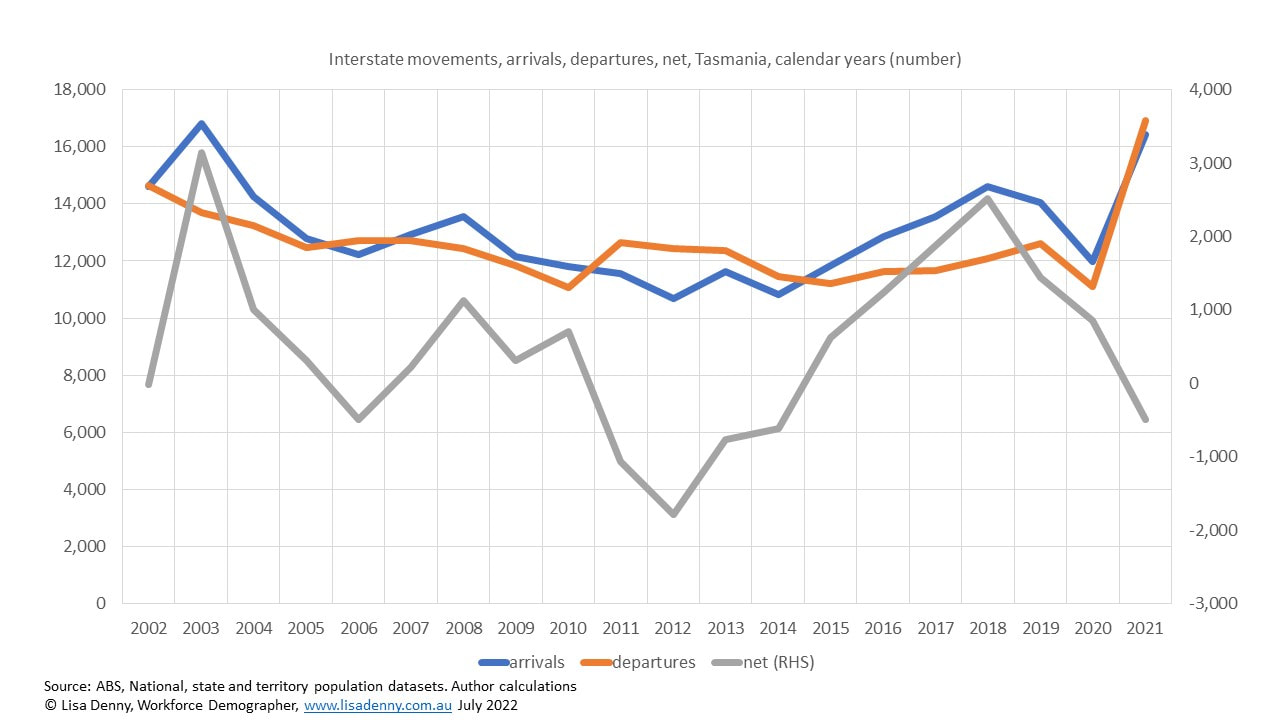

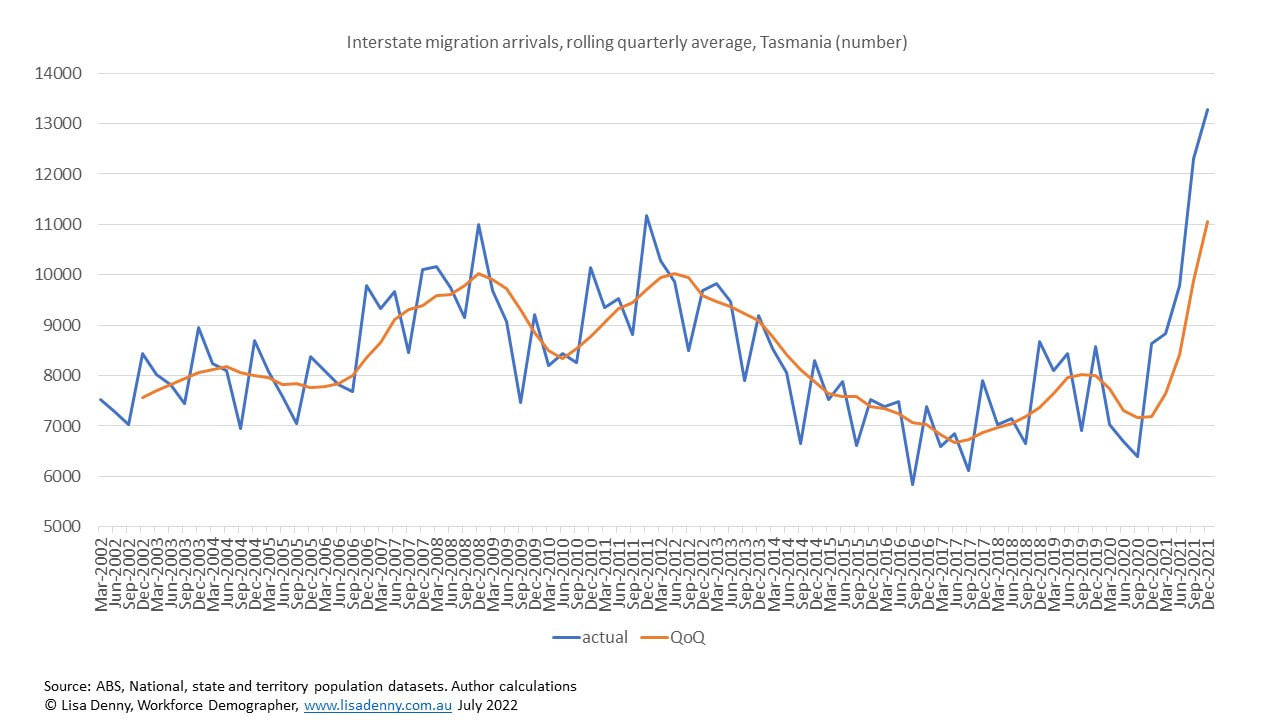

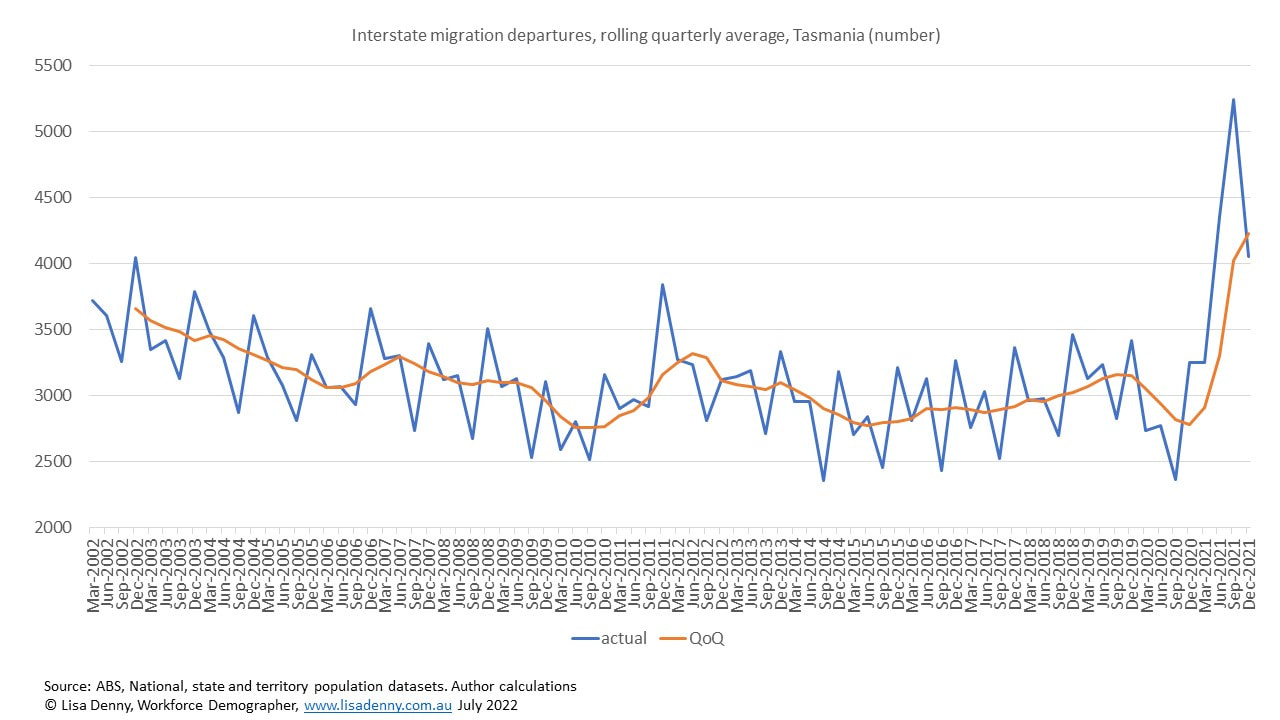

In terms of interstate migration, since the pandemic began in March 2020, 4 out of 6 quarters have recorded net interstate migration loss, including the last two to September 2022.

Population change in Tasmania now appears to be resembling pre-2016 patterns – smaller gains in natural increase (more births than deaths), net gains from overseas migration, and net losses from interstate migration.

So, while Bernard Salt may be an entertaining social commentator, the blatant inaccuracies in his claims about Tasmania’s population change highlight the need for a State Demographer and the need for fact over fiction in informing our decision-making.

Given the tumultuous years that we have experienced since March 2020, it is important that population change is closely monitored and that robust population projections are invested in. This will ensure that the needs of Tasmanians can be planned for, and met, into the future.

Dr Lisa Denny is a Workforce Demographer, Adjunct Associate Professor with the Institute for Social Change at the University of Tasmania and a member of the Expert Panel for the Centre of Population, Australian Treasury.